The gender disparity in research funding.

There is a large gender disparity in the number of research grants awarded in Australia. For years men have won more funding than women. This disparity in success is driven by a disparity in applications, as women apply far less often. Success rates for men and women are relatively close, so policies to reduce the gender disparity in funding should focus on encouraging more applications from women. The idea of limiting the number of applications from men using quotas per institution has been raised.

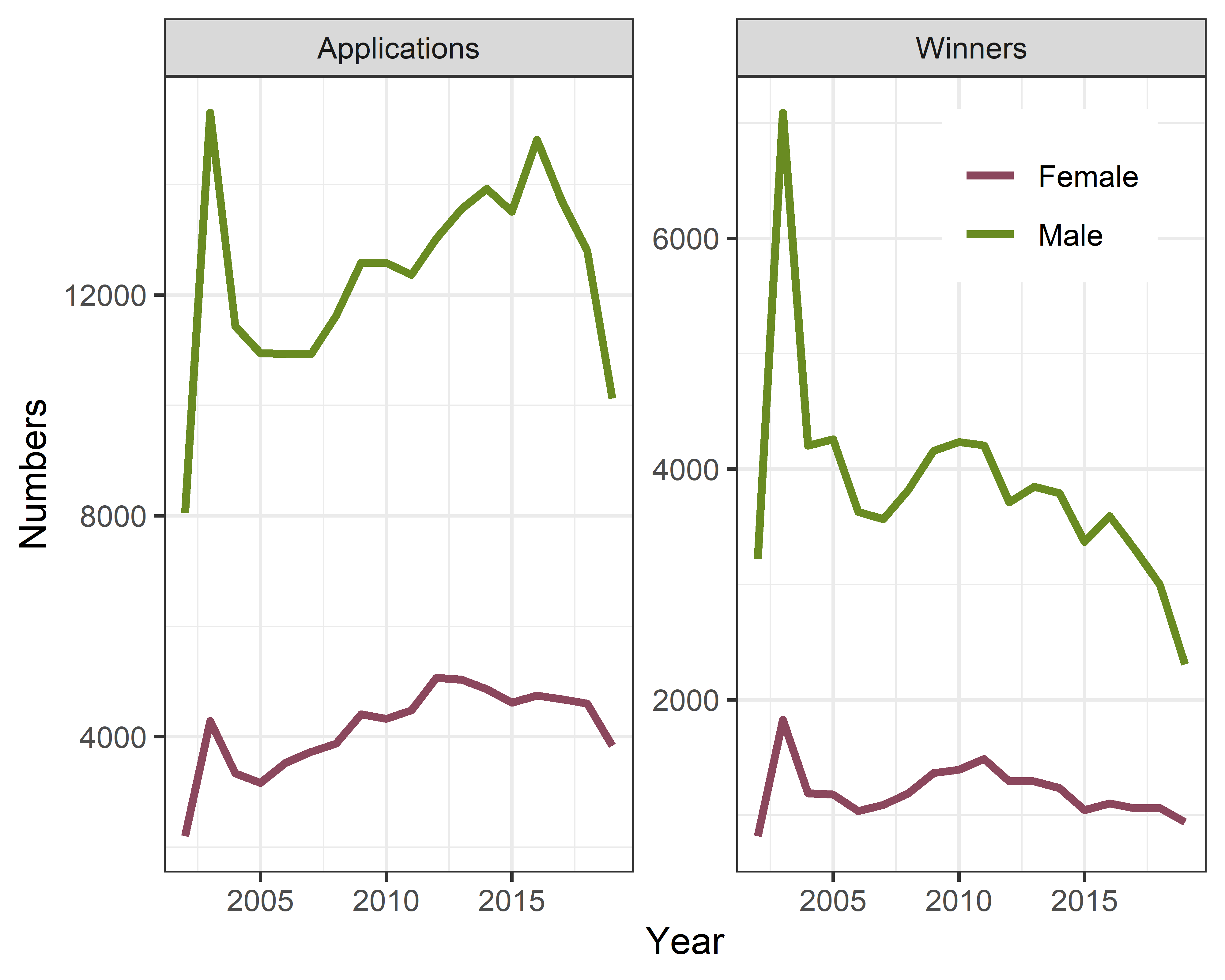

The figures below show the annual application numbers for the Australian Research Council (ARC), with an average gap between men and women of around 8,000 applications per year and around 2,650 awards.1

Funding peer review

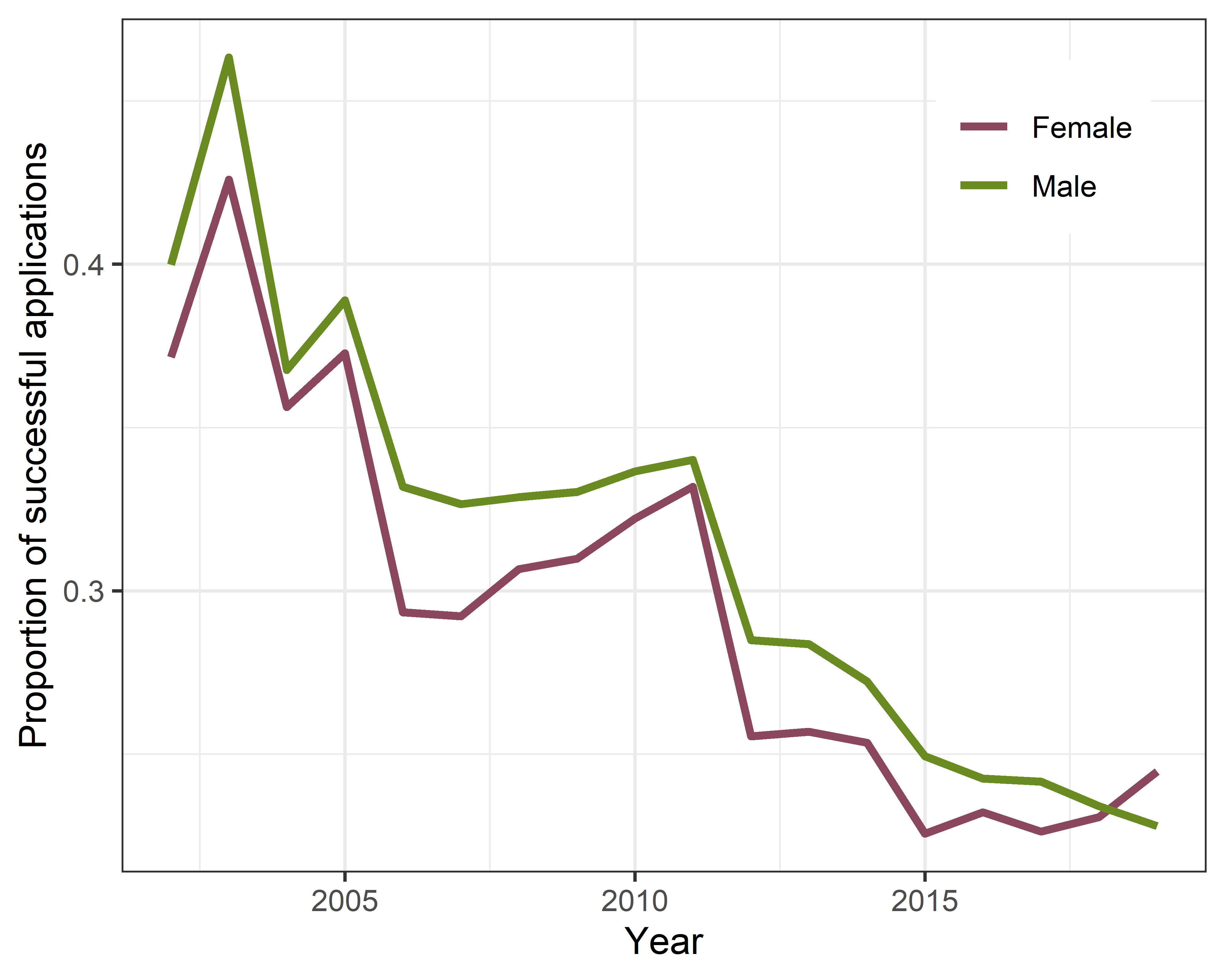

Just in case you are unfamiliar with how research grants are awarded, researchers spend a long time preparing detailed applications, which are then peer reviewed, given a score and ranked. Those ranked high enough win funding, and those below the funding line get nothing. There are lots of different schemes, with some funding projects and some funding people. Most funding schemes work on an annual basis. It’s a tough system and success rates have been falling for years, as shown by the graph below, again using data from the ARC.

Carrying-it-forward

My proposal is to allow women who just missed out on funding to have their score carried forward to the next application round. Women who were close to the funding line (defined below) would be given this option and they could either have their previous score carried forward without having to re-write their application or put in an entirely new application. If they carried forward their score, they would be allowed to update their track record, and this part of their application would be re-scored, meaning their overall score could increase. The deadline for updating track records would be the same as the overall deadline.

Completing a grant application takes a huge amount of effort, we calculated around 20 working days for the lead researcher of an NHMRC Project Grant (Barnett et al. 2015). During this time other work commitments and family commitments often get neglected (Herbert et al. 2014). Some women may choose not to take part because of their other commitments, and hence its often time, not talent, that is the key barrier to success. Knowing that an application could count for two years may encourage more women to take part.

Why not just fund more women?

A direct way of funding more women would be to lower the funding line for them. However, the strong argument against this is that women want to compete on the same terms as men, and such awards would be viewed as less meritorious. Carrying-forward the score keeps the same standards and should fund equally meritorious science, although the association between score and scientific output is weak (Fang, Bowen, and Casadevall 2016).

Simulations

I have simulated the carry-forward policy based on peer review data from the Australian NHMRC from 2009. The data are 6,950 peer reviewers scores for 2,899 applications (two or three reviewers per application). The scores are integers from 1 (worst) to 7 (best), although 1 and 7 are hardly used. Each reviewer gives three integer scores for: significance, track record, and scientific quality. These are combined into an overall score using a 25:25:50 weighting, so scientific quality dominates. The scores for the three reviewers are then averaged to give an average score per applicant, which is then ranked and funding awarded to the highest scoring applicants.

I first fitted a regression model to the real data so that I could simulate lots of alternative worlds. For the details on the model see the technical details below. All the code is available here on Github.

I used a hypothetical scheme with 1,000 applications of which 70% were from men. I assumed the success rates for men and women were the same. Two-hundred applicants were funded per round, a 20% success rate. Each application had five peer reviewers.

I varied the definition of what applications were “close” to the funding line, which controls which women were offered the option to carry-forward their application. I assumed that all women took up the offer. For carried forward applications, I randomly improved their track record by 1 with each reviewer with a probability of 0.5.

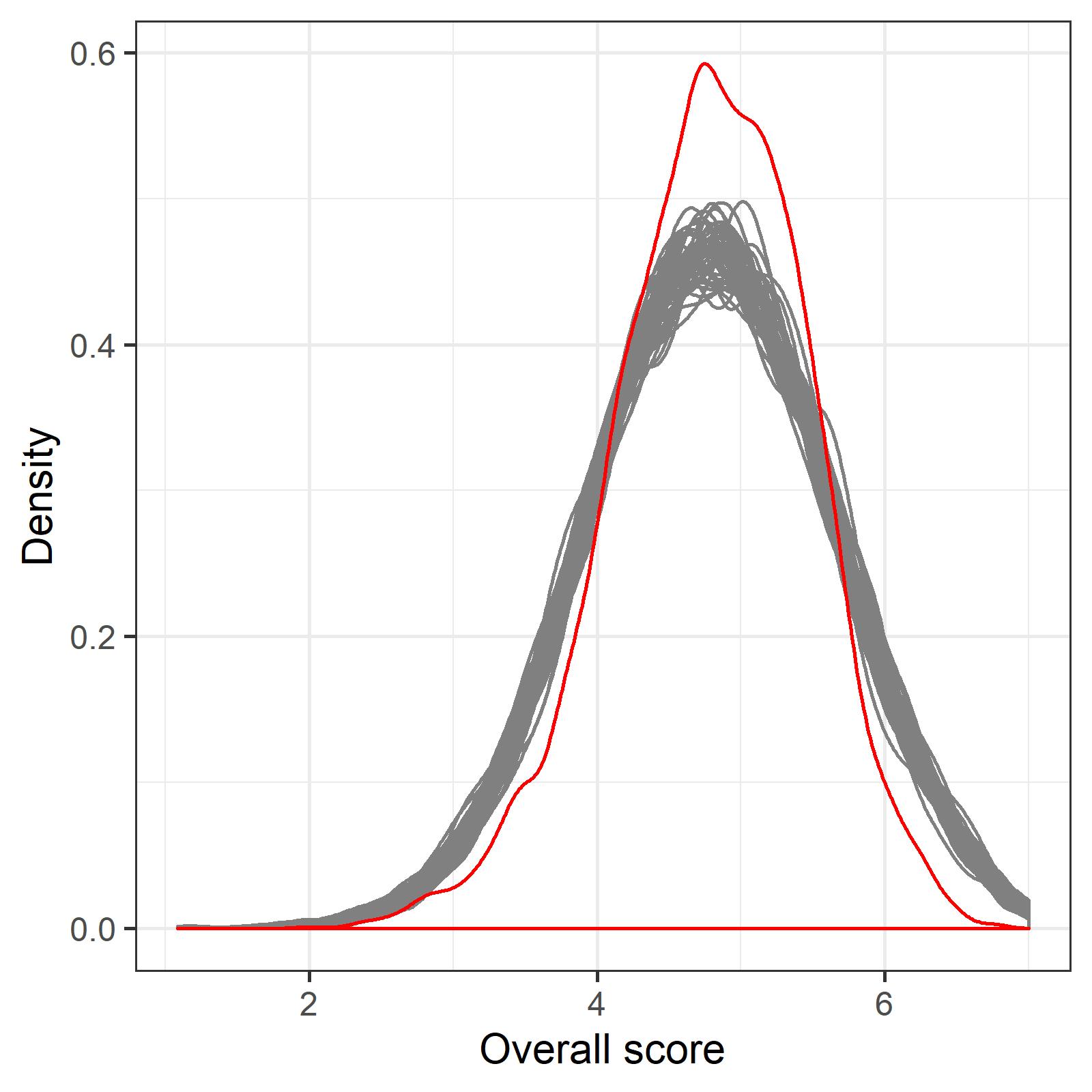

Distribution of overall scores

The plot below shows the distribution of original NHMRC overall scores per applicant (in red) and fifty of my simulations (in grey). My simulations are too smooth and do not match the shape of the original scores, but I am not greatly concerned as I think I capture the broad shape of the scores. The great advantage of using simulations is that we are in complete control, and can change any aspect of the funding system.

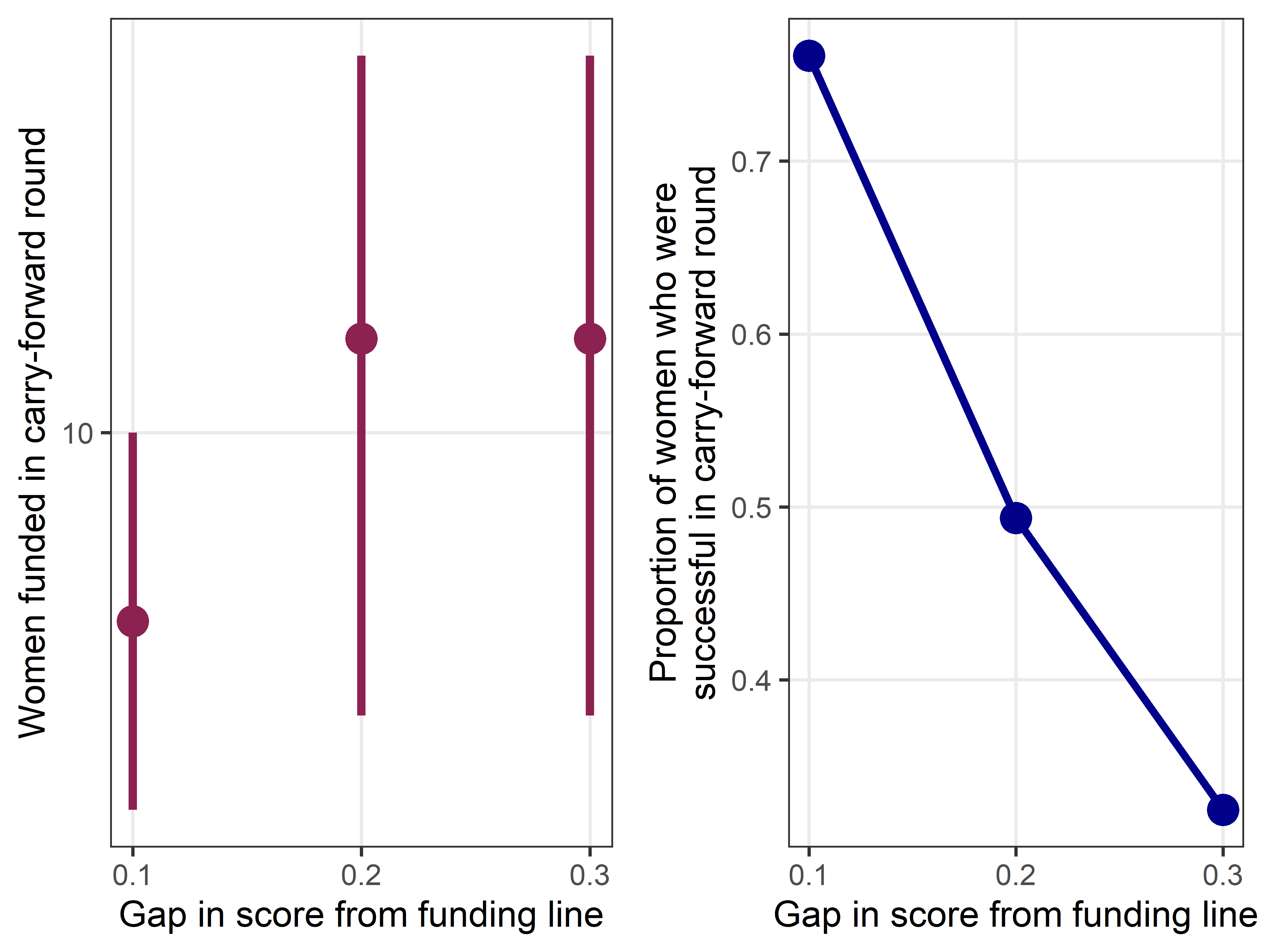

Simulated number of additional women funded

These first results use a female:male ratio of 30:70.

The plots below show the number of women funded by carrying-forward their applications and the success proportion in the second round for the carried-forward applications. The x-axis is the gap between the funding line and those offered the carry-forward. The plots show the median and the inter-quartile range.

A narrow gap in the score of 0.1 leads to a very high success proportion for the carried-forward applications with a proportion of 0.76 funded in the next round. Widening the gap lowers the success rate, because those further from the funding line are included, and by virtue of having lower scores they need more improvements in their track record to get funded. A gap of 0.2 has a success proportion of 0.49 and a median number of 11 women funded by carry-forward. Increasing the funding gap to 0.3 does not increase the number of women funded.

The number of additional women funded is relatively modest at 11 per 1,000 applications, although it increases the absolute number of women funded from 60 to 71 per 1,000 applications.

What if more women apply?

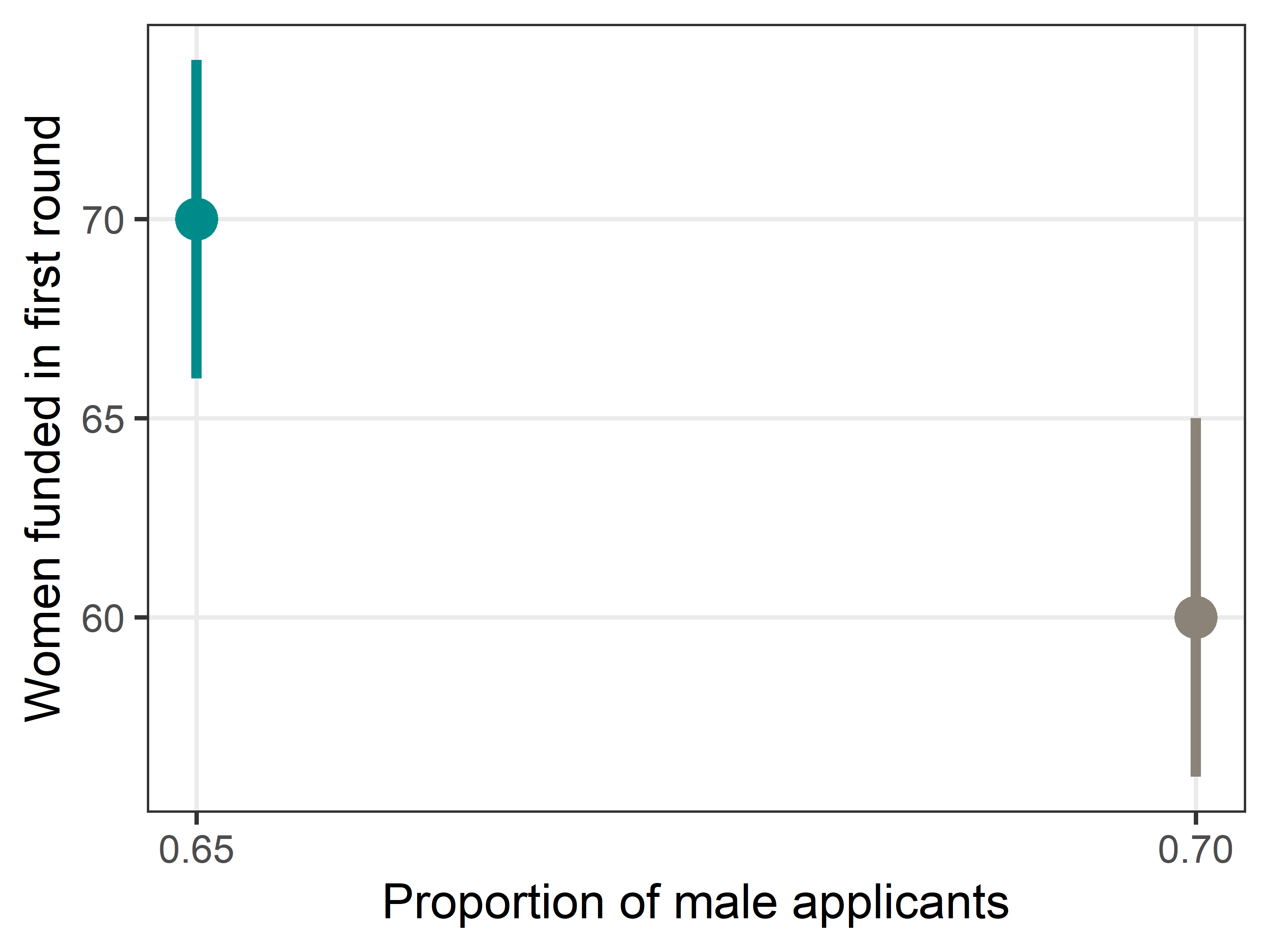

One potential effect of the policy is that more women might apply because they know their application could count for two years. This would mean more women being funded in the first round, and even more women in the carry-forward round too. To model this I changed the female:male ratio from 30:70 to 35:65. The plot below shows the number of women funded in the first round, before the carry-forward (median and inter-quartile range).

So around another 10 women would be funded in the first round. There was a small flow-on to the carry-forward round with an average of 1 extra women funded, so the combined benefit is the 10 women in the first round plus around 12 women from the carry-forward round. So an additional 22 women funded per 1,000 applications.

Summary:

This policy is not going to create the ideal 50:50 balance in research funding, but it would likely fund a good number of additional female researchers for a relatively simple change to the funding process.

Limitations

This is a very simplistic simulation of peer reviewers’ scores with many large assumptions. Given the complexities of the funding system and the often complex behaviour of researchers, the reality could be very different from that shown here.

One complexity I overlooked is that applications are reviewed in panels which have their own funding line (I assumed an overall funding line). This increases the year-to-year variability in the funding line, so I would expect it to increase the variability in the number of additional women funded, but not the average.

One argument against this policy is that a year can be a long time in science and hence the applications may be out of date and so should not be carried-forward. However, most projects and fellowships are 3 years or longer, hence funding systems are already vulnerable to any rapid changes in scientific discovery.

My assumed increase in the female:male ratio from 30:70 to 35:65 is a big jump and may be unrealistic.

I also examined a system in which the weighting was 33% for track record instead of the 25% for the NHMRC model (results not shown), and as expected more women were funded using the carry-forward. A carry-forward based on track record would likely be more effective for schemes where track record had a higher percent of the overall score, the obvious candidate being fellowship schemes.

Technical details of the simulations

I fitted a Bayesian model to the three observed scores for: significance, track record and quality. I assumed these scores were correlated using a multivariate Normal distribution. I assumed that each applicant had a latent overall score that had a Normal distribution.

\(s(i,1:3) \sim \textrm{MVN} (\mu(i,1:3), \Sigma), \qquad i=1,\ldots, N\)

\(\mu(i,j) = \beta(i) + \alpha(j), \qquad i=1,\ldots, N, \, j=1,2,3\)

\(\beta(j) \sim \textrm{N}(0, \sigma^2_{\beta})\)

\(\alpha(j) \sim \textrm{N}(0, 10^2)\)

\(1 / \Sigma \sim \textrm{Wishart}(3)\)

\(1 / \sigma^2_{\beta} \sim \textrm{Gamma}(1,1)\)

In these equations:

-

\(s\)are the observed integer scores for the\(N\)applicants -

\(\alpha\)is the mean score for the three criteria (significance, track record, and scientific quality) -

\(\beta\)is the latent score per applicant.

The model did not converge, because there was a strong correlation between the latent applicant score and the variance$-$covariance matrix for the multivariate normal. This is not surprising as they are related. To get a better convergence I tightened the prior for the latent applicant effect to:

\(\sigma^2_{\beta} \sim \textrm{N}(0.8, 0.01^2)\)

I do not normally do fixes like this, but for a simulated model I am just trying to get average predictions that are as close to the observed data as possible.

The model creates continuous scores, which I converted to integers using rounding. Any simulated scores above 7 were truncated to 7.

Footnote

- Data from https://www.arc.gov.au/policies-strategies/strategy/gender-equality-research/gender-outcomes-ncgp-trend-data - accessed 25-Feb-2020; data for “all scheme rounds announced by Minister”.

References

Barnett, Adrian G, Nicholas Graves, Philip Clarke, and Danielle Herbert. 2015. “The Impact of a Streamlined Funding Application Process on Application Time: Two Cross-Sectional Surveys of Australian Researchers.” BMJ Open 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006912.

Fang, Ferric C, Anthony Bowen, and Arturo Casadevall. 2016. “NIH Peer Review Percentile Scores Are Poorly Predictive of Grant Productivity.” eLife 5 (February). https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.13323.

Herbert, Danielle L, John Coveney, Philip Clarke, Nicholas Graves, and Adrian G Barnett. 2014. “The Impact of Funding Deadlines on Personal Workloads, Stress and Family Relationships: A Qualitative Study of Australian Researchers.” BMJ Open 4 (3). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004462.