Reproduced from the LSE impact blog. Here’s their introduction:

Based on an analysis of over 32 million abstracts published over the last fifty years, Adrian Barnett and Nicole White find a marked rise in common spelling errors. Evidence they suggest of a culture of quantity over quality in academic writing.

Pressure

Many academics feel pressure to publish lots of papers every year because demonstrating their productivity is key for securing jobs and promotions. A striking example of this pressure comes from Nobel laureate Peter Higgs when in 2013 he announced, “I wouldn’t be productive enough for today’s academic system”.

The pressure to publish could mean that thoughtful academics like Higgs are being outcompeted by their more prolific peers. A serious concern is that some academics may be cutting corners to produce papers quickly and remain competitive. Checks of robustness, such as running sensitivity analyses to verify results or waiting for a colleague’s feedback on a draft paper, may be perceived as too time-consuming to warrant delaying publication.

This kind of corner cutting also means that quantity is being prioritised over quality, and the literature is becoming clogged with poor quality papers. One consequence of this information overload is that it is increasingly difficult for academics to be well informed about the best and latest evidence.

Spelling errors on the rise

We examined spelling errors as a simple indicator of corner cutting. Spelling errors are less serious than other bad writing practices, such as plagiarism and spin, but they are easy to check across millions of papers.

We searched for errors in PubMed, which is a popular literature database in health and medical research. We examined over 32 million abstracts published between 1970 to 2023 and looked for spelling errors in the titles and abstracts of published papers, using common errors drawn from our experience as statisticians .

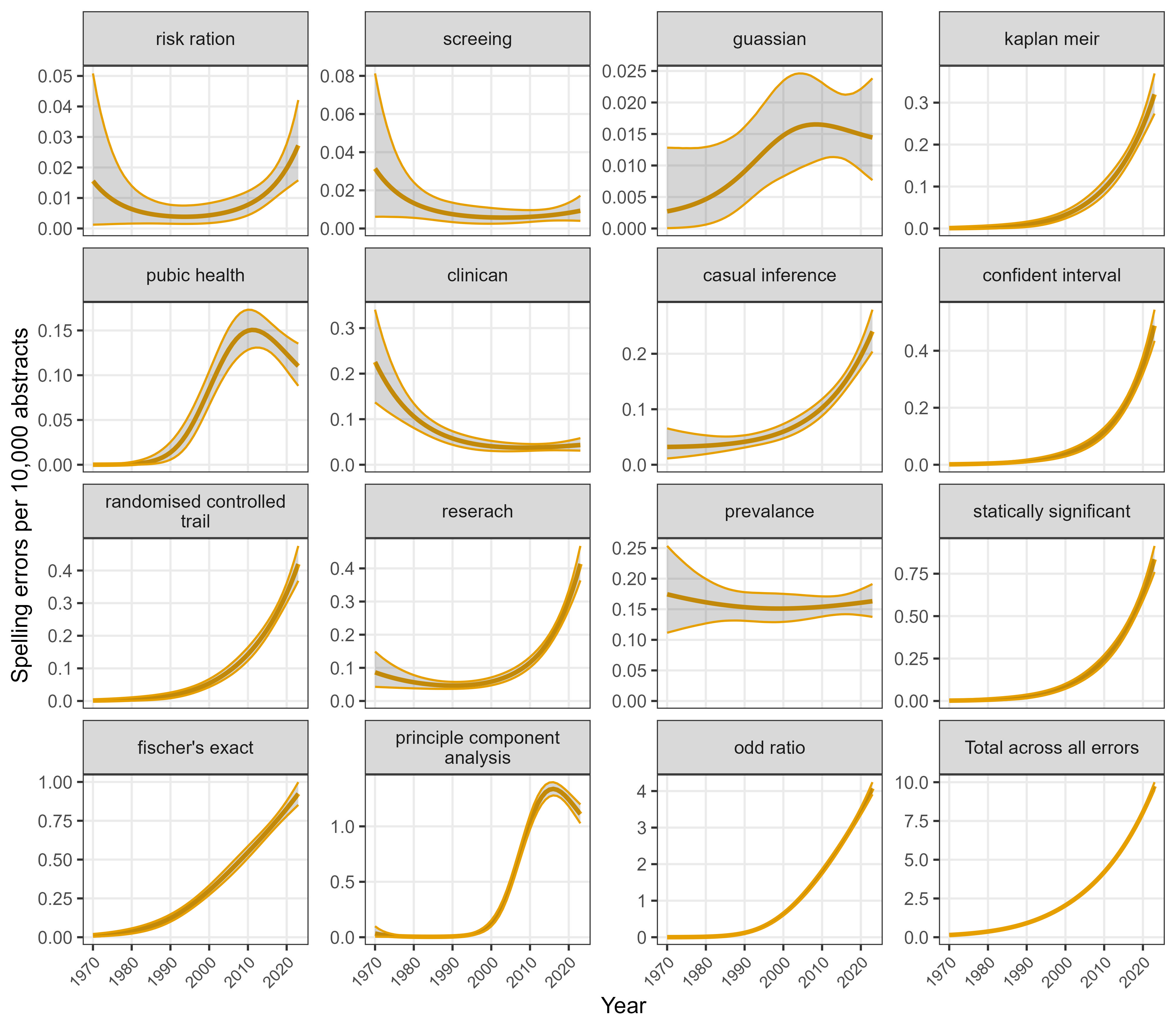

Fig.1 shows these spelling errors and the results. Eleven of the fifteen errors have increased over time, with most showing a strong increase. The total error rate has increased from 0.1 per ten thousand abstracts in 1970, to 8.7 per ten thousand in 2023.

Spelling errors are a symptom of researchers prioritising quantity over quality. We are literally seeing more “casual inference”. The overall error rates are low, however we only examined fifteen errors and these trends are likely to be repeated for other spelling errors, who knows how many ‘teh’s there are in the scholarly record.

Do spelling errors matter?

A spelling error does not undermine the content of a paper, and we have almost certainly published papers with spelling errors. However, these errors are easily avoidable and can be quickly removed using a word processor.

Spell checkers do not capture all errors, for example “odds ration” instead of “odds ratio”, but these mistakes can be detected by proofreading, which should be occurring given that all authors’ final approval is a recommended criterion for authorship. The increase in errors could be due to reduced budgets, with less money to pay for copyediting. There could also be less willingness to wait for professional feedback or a belief that errors will be corrected by publishers.

Authors should want to fix spelling errors, as a paper with many errors shows poor attention to detail and hence harms the paper’s chances of being accepted. When peer reviewers of grant applications in Australia were asked about the characteristics of high-scoring applications one of their criteria was “Well written (no spelling/grammatical errors)”.

Non-native English speakers

Some of the increase in spelling errors is likely due to an increase in researchers with English as a second language, and this increase in diversity and perspective has benefits for academia. We also don’t mean to criticise academics with dyslexia and recognise that academia is often a difficult place for people who do not write in the standard academic style.

Academics from non-English speaking countries could use AI tools to improve their writing and this would also reduce spelling errors. It will be interesting to see if these tools ultimately reverse the trend identified here. However, AI could also become a tool to make writing faster rather than better, and may worsen other writing problems such as vague and derivative text.

Less research, better research

The rise in spelling errors highlights the tension between working slowly and carefully versus publishing quickly. Ongoing efforts to improve research culture should stress the need to commit adequate time to research projects.

The statistician Doug Altman famously called for “less research, better research” back in 1994. Thirty years later we need even less research and much better research. What we don’t need is “reserach”.