Reproduced from the LSE impact blog. Here’s their introduction:

Peer review decisions are definitive, and depending on the style of peer review practiced at a journal, reviewers can usually make one of three recommendations: accept, reject, revise and resubmit. Discussing a new study into the levels of certainty reviewers have making these choices, Adrian Barnett suggests how embracing this doubt could improve peer review processes.

Easy peer review

Occasionally I find peer review easy. It happens when I get a paper with a clear question, that includes a thorough literature review, used a strong study design, presents transparent results, and gives an interpretation that is free of spin. Sadly, such papers are rare, most are a mix of good and bad (in my opinion).

I might like a paper’s premise and be excited about seeing the results, but then read that the authors had to make a big compromise in the design. Are interesting results that might be less robust worth publishing? It can be a difficult call. Should I recommend “Major revisions” and give the authors a chance to respond, or plumb for “Reject” as the paper is not salvageable?

Many reviewers may waiver over their recommendation, and this uncertainty could tell us something about peer review. For example, perhaps longer papers have more uncertainty (on average) than shorter papers, as the more information reviewers have to digest, the harder their task becomes. Or perhaps it’s the opposite, as longer papers mean the authors have provided the details that answer the reviewer’s questions.

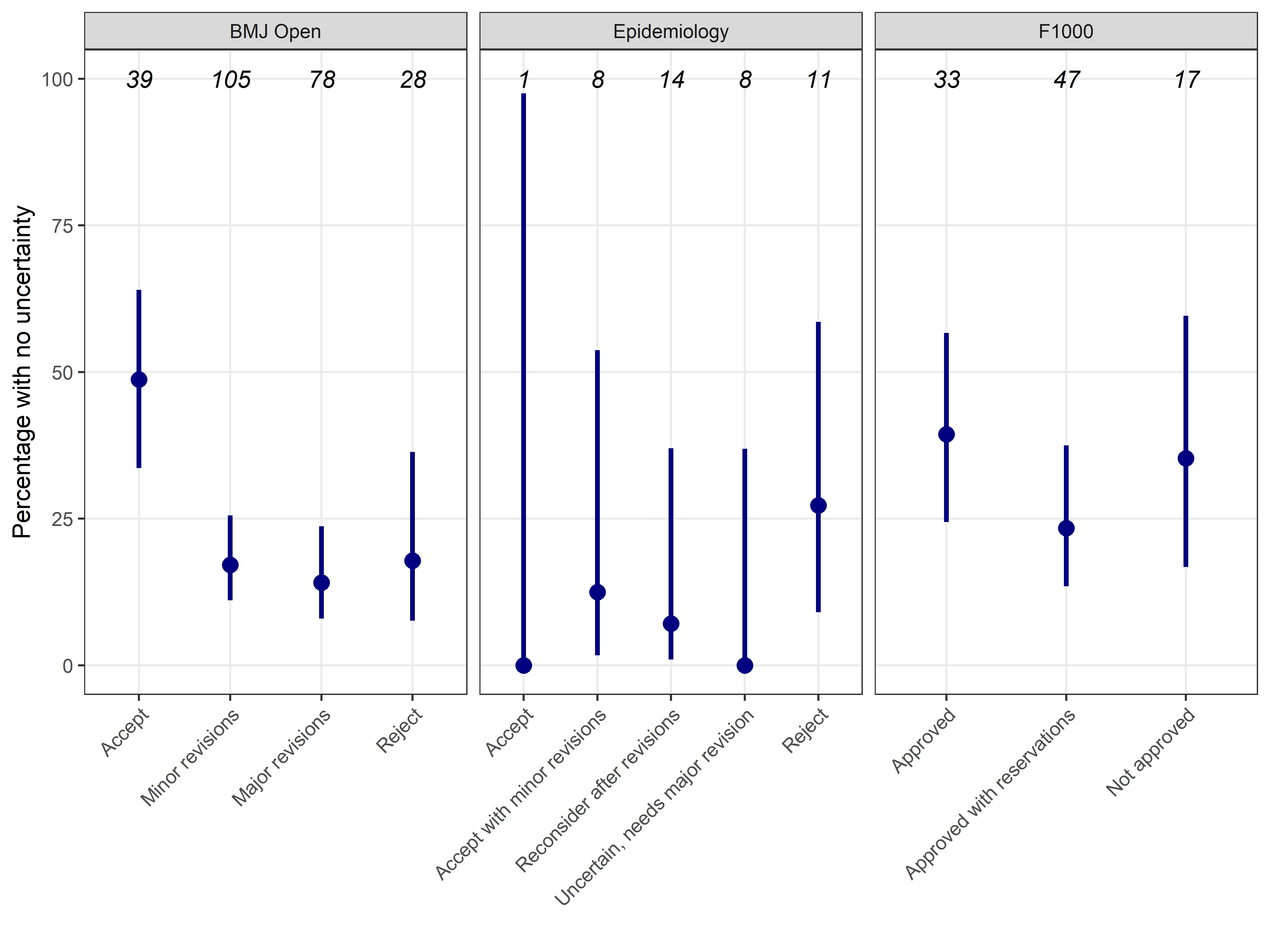

Any decision uncertainty is not captured in a peer reviewer’s recommendation, as they must select a single recommendation such as “Accept” or “Reject”. In a recent study with three journals, we tried to numerically capture uncertainty by asking reviewers to assign percentages to every recommendation, e.g., Reject = 30%, Major revision = 70%, Minor revision = 0%.

Most reviewers experienced some uncertainty as only 23% of reviews had no uncertainty (allocating 100% to a single recommendation). Perhaps this is because most papers are challenging to review, as it is a rare paper that ticks all a reviewer’s boxes. There would also be papers where the reviewer was certain that it was terrible.

Embracing uncertainty

What if all the peer reviewers are uncertain about a paper? Could that mean it’s a potentially ground-breaking finding that should be given a chance? After reading a set of equivocal reviews, the editor’s decision might be based on gut-feeling, and possibly also bias, for example being more generous to high status authors.

Could these uncertain papers be randomised to being accepted or not? This is already happening with funding applications that fall into a decision “grey zone” where the reviewers have not been able to firmly reject or accept the proposal. This is not abandoning peer review, instead it is recognising its limits.

Researchers’ careers are already in the lap of the peer review gods, so why not make that explicit? Randomisation is a statistical bleach that kills unconscious biases, so it would increase fairness.

Brave new journal

It would be a brave journal that makes such a bold change to the status quo. But, the scientific community should embrace innovation. We have over 20,000 journals, and just a handful (that I am aware of) that do anything outside the tried and (con)tested peer review system.

A journal might also benefit from adding some randomisation to their editorial decisions. They might find that the diversity of authors increases, as those authors who have been discriminated against in the current system would be attracted to a fairer system.

They might also find that they get more innovative papers where the authors know that their findings are risky. “Innovation” is a ubiquitous buzzword in the research world, but as well as being a goal it is often also punished by conservative peer review systems that favour incremental progress.

A journal could record the papers that were accepted by lottery or the standard system. They could then follow the papers over time and test for differences in the bibliometrics, such as readership and citations, or examine more detailed measures of impact. This might reveal that a randomised system is no different to the status quo, or potentially better.

Uncertainty about uncertainty

There was a nice meta moment when the reviewers for our paper on uncertainty had to consider their own uncertainty about our paper. One reviewer found some humour in their reflection:

“Why does reviewer #2’s assessment differ than the other two reviewers; and now, with this paper, why can’t reviewer #2 agree with themselves!”

Not all uncertainty is bad, as it might reflect genuine uncertainty about a paper’s merits or the reviewer’s humility about the limits of their understanding. Ideally, we want a peer review system where bias is reduced to zero, but there will always be some uncertainty. If journals and funders are willing to measure uncertainty, then we could learn more about peer review systems and where they could be improved.